Most students make flashcards wrong. They either copy entire paragraphs (too long to review efficiently) or create hundreds of cards for every bold term (too shallow to build real understanding). This guide shows you how to extract the right information from textbooks and structure it for effective learning.

Good flashcards from textbooks aren't about coverage—they're about identifying what's worth remembering and structuring it for retrieval practice. Done right, you'll spend less time making cards and more time actually learning.

Summary

- Focus on high-yield content: definitions, processes, comparisons, and common mistakes—not every fact in the chapter.

- One idea per card. If a card takes more than 10 seconds to answer, split it.

- Use your own words. Paraphrasing forces processing and creates stronger memories.

- Quality over quantity: 30-50 well-crafted cards beat 200 low-effort cards.

What makes textbook flashcards different?

Textbooks contain far more information than you need to memorize. They explain concepts, provide examples, offer context, and include details that help you understand but don't need to be recalled on command.

Your job is extraction—pulling out the essential, testable, memorable content while leaving behind the explanatory scaffolding. This requires reading actively and making decisions about what's worth a card.

What content deserves a flashcard?

Definitions and key terms

If your textbook bolds a term or explicitly defines something, it's probably testable. But don't just copy the definition verbatim—rewrite it in your own words to force processing.

Bad card: "What is mitosis?" → [copies 3-sentence textbook definition]

Good card: "What is mitosis?" → "Cell division producing two identical daughter cells (somatic cell reproduction)"

Processes and sequences

Multi-step processes need multiple cards. Break them down so each card tests one step or transition.

For a process like protein synthesis:

- Card 1: "What happens in transcription?" → "DNA is copied to mRNA in the nucleus"

- Card 2: "What happens in translation?" → "mRNA is read by ribosomes to build a protein"

- Card 3: "Where does transcription occur?" → "Nucleus"

- Card 4: "Where does translation occur?" → "Ribosome (cytoplasm or rough ER)"

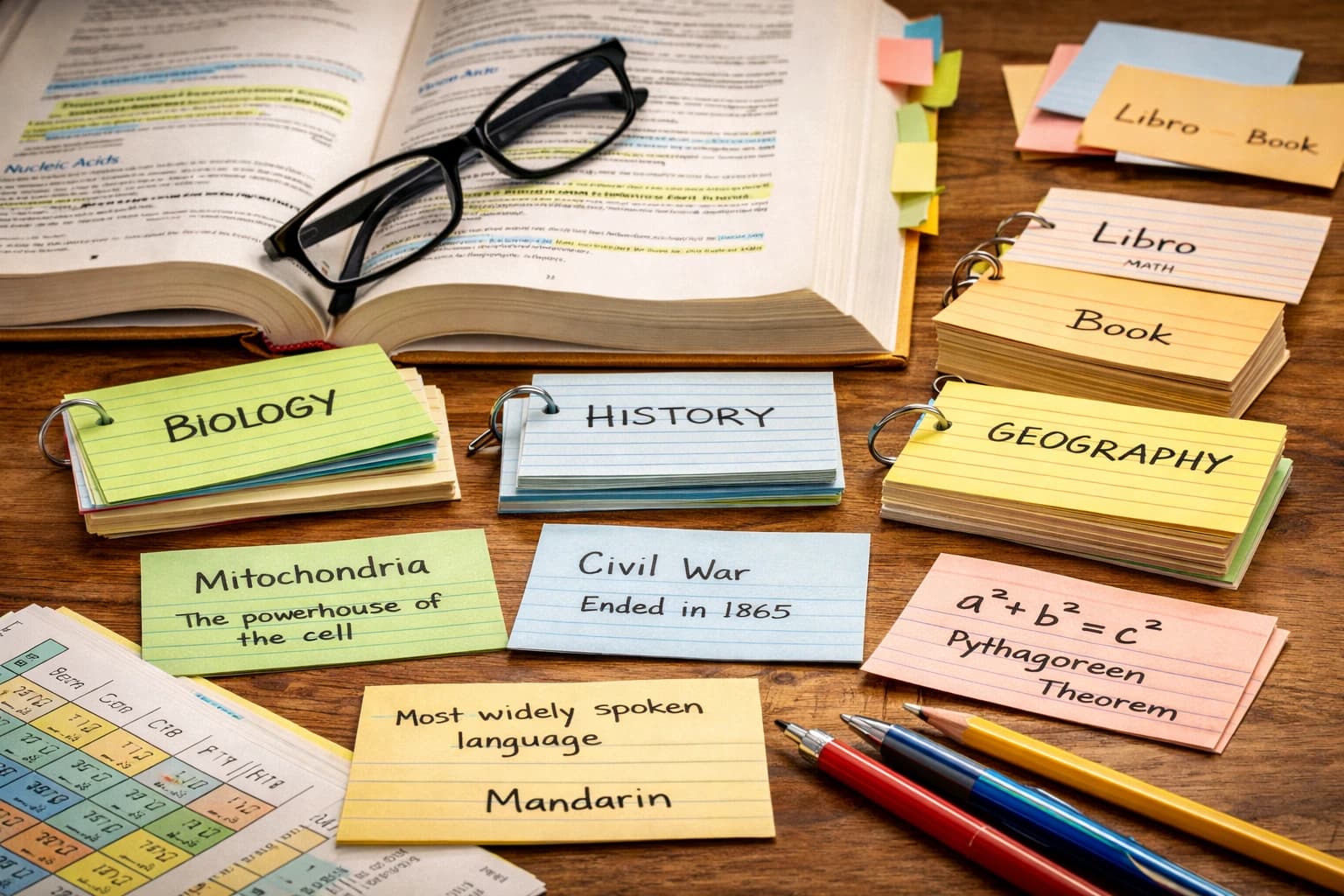

Comparisons and distinctions

Textbooks often compare similar concepts. These distinctions are frequently tested.

Example: "How does mitosis differ from meiosis in terms of daughter cells?" → "Mitosis: 2 identical diploid cells. Meiosis: 4 different haploid cells."

Causes, effects, and relationships

Understanding why things happen is often more important than knowing what happens.

Example: "Why do cells undergo apoptosis?" → "Programmed cell death eliminates damaged, infected, or unnecessary cells"

Common mistakes or exceptions

If your textbook explicitly mentions "a common misconception is..." or "except when...", make a card. These appear on exams.

What should you NOT make flashcards for?

- Examples used to illustrate concepts: Understand them, but don't memorize specific examples unless they're famous or frequently referenced.

- Contextual explanations: "Scientists discovered this by..." is interesting but rarely tested.

- Redundant information: If you already have a card for a concept, don't make another card that tests the same thing differently.

- Information you already know: Don't waste review time on cards you'll always get right. Focus on what's new or difficult.

- Highly specific numbers (usually): Unless a specific date, measurement, or statistic is emphasized as important, general understanding beats memorizing exact figures.

How should you structure your flashcards?

One atomic idea per card

Each card should test exactly one piece of knowledge. If you find yourself writing "and" or listing multiple items, you probably need multiple cards.

Bad: "What are the functions of the liver?" → [lists 5 functions]

Good:

- "What organ produces bile?" → "Liver"

- "What organ detoxifies blood?" → "Liver"

- "What organ stores glycogen?" → "Liver"

Yes, this creates more cards. But each card is fast to review and precisely identifies what you do or don't know.

Keep answers short

Answers should be one sentence or less—ideally something you can say out loud in one breath. Long answers are hard to self-grade and don't practice efficient recall.

Make questions specific

Vague questions allow vague answers. Compare:

- Vague: "Describe photosynthesis" (could say anything)

- Specific: "What are the inputs of photosynthesis?" (must answer: CO2, H2O, light)

Add context when needed

Sometimes a term appears in multiple contexts. Add clarifying context to your question.

Example: "In genetics, what is a dominant allele?" vs just "What is dominant?"

What's the workflow for creating flashcards from a chapter?

Step 1: Read actively first

Read the chapter with a highlighter or make notes. Mark definitions, key processes, comparisons, and anything emphasized. Don't make cards during this read—you need the full picture first.

Step 2: Identify card-worthy content

After reading, review your highlights and notes. Ask: "What from this chapter might appear on an exam?" and "What do I need to recall on command?"

Most chapters have 30-50 card-worthy items. If you're making 100+ cards per chapter, you're probably including too much.

Step 3: Write cards in your own words

Translate textbook language into your language. This forces you to actually understand the content and creates cards that match how you naturally think and speak.

Step 4: Review and refine

After creating cards, do a quick review. Cut any that are too long, too easy, or redundant. Better to have fewer high-quality cards.

Tools that speed up the process

If you have digital textbooks or PDF lecture slides, you can use AI tools to accelerate flashcard creation:

- PDF to Flashcards - Upload your textbook chapter or notes and get AI-generated flashcards you can review and edit

- Image to Flashcards - Take photos of textbook pages or diagrams and convert them to cards

AI-generated cards aren't perfect—you should review and edit them—but they're a massive time-saver compared to typing everything manually.

How many flashcards should you make per chapter?

There's no universal number, but these guidelines help:

- Introductory chapter: 20-30 cards (mostly definitions)

- Process-heavy chapter: 40-60 cards (processes break into many steps)

- Review/synthesis chapter: 10-20 cards (mostly connecting previous concepts)

If you're consistently making 100+ cards per chapter, you're likely including too much detail or not atomizing properly.

How do you review textbook flashcards effectively?

Creating cards is just the first step. The real learning happens during review.

- Use spaced repetition: Review new cards daily for the first week, then extend intervals based on how well you remember. See our spaced repetition guide for details.

- Be honest in self-grading: If you hesitated or had to think hard, mark it wrong. You'll see it again sooner.

- Say answers out loud: Verbalizing activates different memory pathways than just thinking the answer.

- Don't skip hard cards: The cards you avoid are exactly the ones you need to study most.

Common mistakes when making textbook flashcards

- Copy-pasting textbook text: Verbatim copying skips the processing that creates memory. Always paraphrase.

- Making cards as you read: You need context to know what's important. Read first, make cards second.

- Testing recognition instead of recall: Cards that show a term and ask you to recognize the definition are backwards. Show the definition, recall the term (or vice versa).

- Not reviewing regularly: A deck of unreviewed flashcards is just a collection of digital paper. The value is in the review.

- Making cards for everything: More cards isn't better. Focus on high-yield content that's likely to be tested or that you struggle to remember.

Wrap up

Effective textbook flashcards come from selective extraction, not comprehensive coverage. Focus on definitions, processes, comparisons, and common mistakes. Keep cards atomic and answers short. Use your own words.

The time you invest in creating good cards pays off during review—well-structured cards are faster to study and more effective for building lasting memory. If you want to speed up the creation process, try uploading your textbook PDFs to generate a starting set of cards you can refine.

Frequently Asked Questions

Should I make flashcards while reading or after finishing a chapter?

How many flashcards should I make per textbook chapter?

What should I include on a textbook flashcard?

Related articles

Continue learning with these related posts.

Put these techniques into practice

Upload your study materials and let Laxu AI create flashcards, notes, and quizzes automatically.